This started as a post on Instagram to raise awareness of the issue of Adverse Childhood Experiences and how they can impact Third Culture Kids. Then I thought it would be helpful to include it here in the blog as reference material. What I didn’t expect, was that I would go so far down a rabbit hole that I would have to be pulled out backwards. I still feel like I’ve only scratched the surface of this subject but decided that it was a good start. I will update as more research and data becomes available.

It got longer than expected so if you just want the summary, jump to here. Perhaps then you will be so intrigued you will return to read the whole article 😉

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

According to the CDC Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) are potentially traumatic experiences before age 18 that can lead to a host of physical and mental health problems in adulthood. They undermine a child’s sense of stability and safety and can have life long detrimental effects.

They include any form of abuse, experiencing and witnessing violence, loss of a loved one, parent’s mental health issues, parent’s substance abuse, poverty, grief, racism and xenophobia to name some. ACEs are grouped into three categories: household, community and environment.

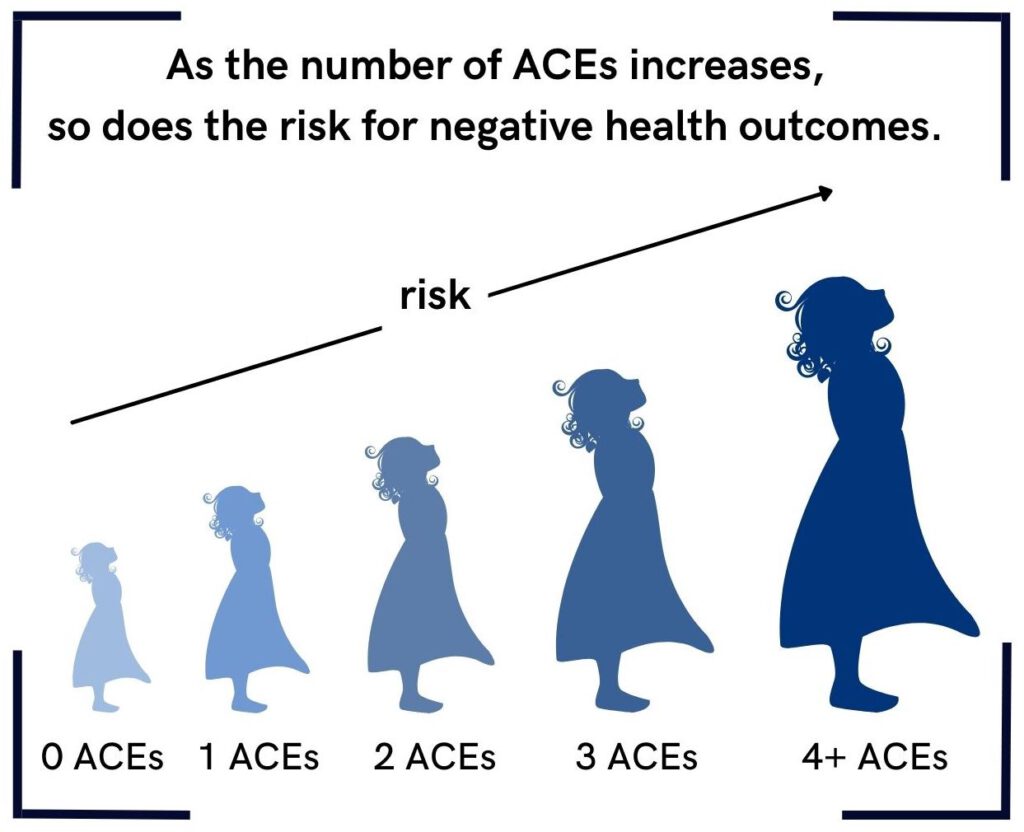

The link between health issues (mental and physical) and ACEs is so strong, that a you can calculate it. One point for each type of trauma experienced = ACE score, which is correlated to the risk of health and social problems. The experience of trauma is so impactful that it can change brain function and impact our immune system, more on this below.

What are the consequences of ACEs?

ACEs effect an individual’s health and wellbeing. Health and social problems in adulthood start to appear with 1 ACE and become progressively more likely, the higher the ACE score. For example, in the general population of the USA a score of 1 increases the probability of chronic depression from 18% for men and 11% for women to 23% and 19%, respectively. A score of 3 sees a jump to 42%/30%.

The rates of attempted suicide jump from 2% with an ACE score of 0 to >10% with an ACE score of 3 and nearly 20% when ACE is 4+.

Liver disease goes from 5% in the general population with an ACE of 0 to 10% in people that experienced 3 ACE in childhood. Problems performing a job consistently increase from 5% (ACE: 0) to >15% (ACE: 4). The list goes on – perpetrating violence, chronic lung disease, addiction, social problems, being a victim,… studies show that nearly all chronic physical, mental, economic and social health problems experienced by humans worldwide are linked to trauma experienced in childhood.

The effects of ACEs don’t always wait until adulthood though – “we see young children with behaviour issues, developmental delays,… and other barriers to typical growth” (source). It is also important to note that the type of ACEs experienced is irrelevant, just the number. The brain cannot differentiate the kinds of trauma and stress.

(Data used from here.)

Who experiences ACEs?

From the first studies of middle class, college educated US-Americans in the late 1990s to the most recent studies of all races, ages, and economic classes worldwide the answer is: everyone.

In large scale studies in the USA about 61% of adults surveyed across 25 states reported that they had experienced at least one type of ACE, and nearly 1 in 6 reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs (source). Smaller studies in China uncovered low rates of ACEs in 65% of young adults and nearly 1 in 10 had experienced multiple ACEs in childhood (source). Two vastly different cultures – very similar results.

Expat Child Experience

There is currently no completed study that can provide us with data on how Third Culture Kids experience ACEs and which of them are most common. TCK Training completed a large survey last year and is currently compiling data. As it becomes available, I will update this section.

Until then, we must look at circumstantial evidence and personal experience. I will share some excerpts and quotes here:

A study published in the International Journal of Metal Health found “The study concludes that employees living and working as expatriates experience a higher range of risk for mental health and substance use disorders that exceeds their U.S. counterparts.” (source)

Lauren Wells from TCK Training: “…it has become clear that TCKs are at high risk for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and developmental trauma. ” (source)

Rebecca Grappo says: “belonging, recognition and connection. For TCKs, these basic needs are ripped away with each move. Powerless in the decision to relocate, their many losses are often not acknowledged even by their own parents, and the main problem is unspoken, unrecognized, shunted aside.” (source)

Ruth van Reken (co-author of Third Culture Kids and lifetime advocate for cross-cultural kids): “unresolved grief is the most urgent mental health issue facing TCKs — the children as well as the adults they will become.”

The stress of repeated moves and many unresolved, unexpressed losses compounds for some TCKs, causing toxic stress and trauma. Experiences that can be classified as ACEs specific to the TCK experience (as mentioned in The Grief Tower by Lauren Wells) may be:

- experiencing violence (at home or witnessing it, e.g. in a host country),

- unmet needs for belonging and community,

- parent’s mental health problems (studies show these to be 2.5times higher than for the general population),

- divorce,

- physical abuse at the hands of caregivers or school and

- sacrificing their emotional needs to the pressure of the family to “perform”,

- loss of connection to grandparents or other close family members/friends.

Taken together this all indicates that expats and their children experience higher overall levels of stress and ACEs than the general population. This is a clear call to action and warning for everyone caring for international children.

Toxic Stress

The CDC describes toxic stress as continued, prolonged stress and further elaborates that toxic stress from ACEs can change brain development and behaviour such as learning and stress responses.

In her book Raising Global Teens, Dr. Anisha Abraham explains how toxic stress affects the brain and physical development of teens in particular: “For those who are exposed to high doses of adversity in childhood, the pleasure and reward center of the brain … can be significantly affected. As a result, individuals fell less pleasure and need higher and higher doses, which in turn lead to risky behaviours and substance dependence.”

She goes on “ACEs can impact the immune system and put teens at risk for chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases like asthma.” Perhaps most surprising to a lay person is that “exposure to ACEs can shorten telomeres and cause premature cellular aging.” This explains why people that experience ACEs of 4+ have a significantly lower life expectancy than the general population.

It should come as no surprise then that children that experience trauma (as a single event or compounded through ACEs) are sometimes misdiagnosed as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Their brains have been altered to the point where they are having difficulty regulating their behaviour.

Mitigating and Preventing the Effects of ACEs

While this is all frightening and important to know, we also need to be aware that there are measures we can can take individually and as societies to prevent and mitigate ACEs and their effects on children and the adults they become. There are two major areas of work: prevention and care.

Prevention

The first step is awareness and prevention. Vetting people we spend time with and situations we send our expat children into can help avoid traumatic experiences. While I am in no way advocating locking kids up at home, we cannot assume that what is the norm regarding safety and behaviours in our home country is the same in our host nation. Research and asking around about what to expect and then discussing with your children is a first step.

Corporal punishment is sadly still practiced in some country’s schools and by nannies and care takers. Do your research, be clear on your expectations of these people and check-in with your children regularly.

Parents need to know which of their behaviours could be an ACE and take measures to change these. This includes looking after your own mental health and patterns of addiction, creating a post-divorce family life that is non-toxic, and putting your children above work commitments.

Understanding and meeting our children’s needs for community and belonging as well as attention and care is key to eliminating ACEs caused by unmet needs.

Care and Building Resilience

ACEs can be mitigated and their effects reduced by Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs). These are all the good experiences and the people in a child’s life that care deeply for them, believe in and support them.

Supportive, understanding parents, a grandparent that shows love and care consistently, a teacher that believes in a child, a friend to confide in, a neighbor that trusts them to look after her pet – research shows that it only takes one caring adult to change the trajectory of a child’s life (source). These are all PCEs that will help strengthen a child’s confident and trust, reduce stress and give them a way to balance out some of the effects of ACEs.

As an expat family having strong, supportive family bonds that accept children and places them at the core of what they do is a shield. Helping our children process their grief, all those incidences of unresolved grief through many goodbyes and transitions, reduces their levels of toxic stress. With knowledge and tools parents can do this with their children.

Resilience is also a key component in mitigating ACE impacts. According to Dr. Ginsburg, Professor of Pediatrics, “Young people will be resilient, when important adults in their lives believes in them and hold them to high expectations. (source)” . Harvard researchers agree. They found that the single most common factor for children who develop resilience is at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive adult (source).

What you can do

Both the Harvard study and Josh Ship agree it’s never too late to start and the most important factor in mitigating effects of ACEs is having supportive adults in their life that believe in them and invest in the relationship.

While a child’s brain and biological systems are most adaptable in early life, it is never too late to start caring for a child and it is never too late to build resilience. There is time left, whatever the age of the child, and we should use it wisely.

An adult in a child’s life that is actively working on their resilience and other healthy behaviours is not only caring for themselves, but also teaching by example, thereby setting a new pattern in motion.

Parents

As a parent you might be feeling overwhelmed after reading this. But the good news is, there are things you can do:

- learn about ACEs and reflect on which of them may affect your children and what you can do to eliminate them.

- check-in with your children. Find a way that works for your family, e.g. at the dinner table, in the car, at bedtime, ask “on a scale of 1-10…”

- think carefully about the people your children spend time with. Talk to them about your expectations. Talk to your children about keeping safe.

- speak to school(s) about their policies for identifying ACEs and e.g. their bullying policy.

- find out details of care and behaviour before you let them join activities and field trips.

- when leaving them with carers, make sure they can communicate with them. Powerlessness due to lack of an ability to communicate needs and wishes can cause stress.

- show them by your actions that they are more important than the work you are on assignment to do.

- give them opportunities to make decisions and have a voice. Having some measure of control in their life can also be a PCE.

- give them safe spaces to try and succeed at hard things (thus building resilience and belief in themselves) – if they fail, help them reflect, refocus and try again.

- take care of your own mental health & detrimental behaviours

- take care of yourself physically

- strengthen your family connections and bonds to build a strong sense of belonging and stability.

- understand the stresses and sources of unresolved grief that growing up abroad can bring with it. Learn how you can help your children process grief and loss.

- these posts on moving internationally with kids also cover actions to take.

Note: I’m offering a free talk on the Foundations of Raising TCKs on 20. January that’s a good starting point for parents wanting to know more about the risks and opportunities and what you can do as a family to build stronger connections. I also offer individual coaching and training sessions for parents or the whole family (e.g. Expat Family Flight School). Please contact me if you’re interested in any of these.

Friends & Family

Remember, parents aren’t the only option for supportive adults in a child’s life. If you don’t have children with you on assignment you have the unique opportunity to help out. Parents are often maxed out just trying to care for the basic needs of everyone. Building trusting relationships with other adults is an important life skill that is sometimes hard to learn for children living a transient life. Obviously be respectful of parents’ wishes and explain your thoughts to them when you offer your help.

For grandparents and extended family living elsewhere it can be hard to build a close, supportive connection but certainly not impossible. Staying in touch regularly and showing an active interested in the child’s life, their friends and likes & dislikes can go a long way towards having strong connections. Read this post about long distance connections for more ideas.

Sending Organizations

Employers can do a lot to care for the family of their assignees and it all pays off (see here for some data). Some best case examples include: implementing care & training plans for all stages of the assignment and actively including family members; providing easy access to mental health care for all family members; and doing safety checks of homes and schools can also be helpful. Providing and nurturing a local community of your expat families is also a huge step towards better care for children and the whole family. These are a few ideas at the tip of the iceberg.

Please contact me if you are interested in setting up a more comprehensive family-inclusive global mobility program.

Summary

ACEs affect a large portion of the general population and presumably at least as many TCKs. The effects of ACEs on children and the adults they become are manyfold – ranging from altered brain structure and changed behaviour patterns to social problems and a myriad of mental and physical health issues. ACEs are observed across all races, ethnic groups, classes and cultures worldwide.

Some ACEs can be prevented through awareness and changes in the family or community situation.

The negative effects of ACEs can be mitigated through Positive Childhood Experiences, which include helping children build resilience, processing loss & grief and having supportive adults in their lives. Every day counts and it’s never too late to begin.

Not sure where to start? I always start with research and information gathering. My free talk on the Foundations of Parenting International Kids is a good jumping-off point. Other references (websites & books) can be found at the end of this page.

Sign up for my free talk on the Foundations of Parenting International Kids to learn about the challenges and benefits of growing up abroad and how you – as a parent – can support your child.

Online Resources & References

- ACES Primer video

- ACEs Too High – very informative website with summaries of many studies.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA)

- International Journal of Mental Health – The Mental Health Status of Expats vs US Domestic Workers

- Jordan Institute for Families

- Josh Shipp – One Caring Adult

- Dr. Kenneth Ginsburg – Fostering Resilience

- npr – ACE Quiz and What it Does and Doesn’t Mean

- The Lancet (Wales) – Comparative study including data from UK, Saudia Arabia & USA

Books referenced

- Third Culture Kids, David C. Pollock, Ruth E. Van Renken, Michael V. Pollock

- Raising Up a Generation of Healthy Third Culture Kids, Lauren Wells

- Raising Global Teens, Dr. Anisha Abraham

- The Grief Tower, Lauren Wells

Pingback: How to move abroad with children - Global Mobility Trainer

I’m very impressed with your research and writing. This is indeed a very important topic. I’m reminded of something I read once: a child with positive support will do well in school; a child with negative support will still mostly succeed. The child who is ignored will almost always fail.