Why bilinguals detest autocorrect and family gatherings

Why bilinguals detest autocorrect and family gatherings

Being bilingual is übercool, isn’t it? Instead of having to learn a foreign language from scratch like most monolinguals who spend hours memorising verb tables (gehen, ging, gegangen), you are already able to sing along to songs and watch TV programs from two or more cultures! And it’s great when you are on public transport and you can code-switch to secret language so that nobody knows what you are talking about – not even James Bond could do that, could he?

So is bilingualism as effortless as it sounds? I know many parents who have managed to raise children to speak two or three languages and others who have given up along the way. Bringing up children bilingually actually takes a lot of commitment and consistency. I know it as I’ve been there, done it and yes, I now have two wonderful bi-cultural and bilingual children that move in and out of languages and cultures with the flexibility of a Pilates instructor.

When my children were younger I was often told how lucky I was to have kids who could speak more than one language. They were born in Austria, their Dad is Austrian and I’m British and sometimes they had to act as interpreters between their English and Austrian grandparents. I’m not sure they felt particularly lucky at the time, consecutively interpreting on topics such as politics and hydroelectric power stations from one grandfather to another. And for me as a parent, helping them with Maths in German was a painful affair – me barely remembering the order of operations BODMA rule in English let alone its German “KLAPUSTRI” equivalent? Hilfe!

On occasions bilingual kids fall through the net in education systems. My own children were born in Austria and only spoke English to me and my family, they didn’t go to an international school. They had English lessons of course where they sounded great but didn’t get higher marks than their Austrian counterparts as they couldn’t give a monkeys whether they were using the present simple as opposed to the present progressive let alone identify it in a gap-fill exercise. Other than that their fluency was brilliant but there wasn’t a “brilliant” box to tick on a school report!

Repatriating to the UK and having them then experience the joys of the British school system as teenagers, they had meltdowns about their peers using sophisticated vocabulary and with science not being a major subject in Austria, just a “Nebenfach” (side subject), their brains were reeling trying to get to grips not just with Physics but the language of Physics. And once again, the British education system (like most school systems) is based on a system introduced by the Victorians and let’s face it, what did the Victorians know about bilingualism?

Repatriating to the UK and having them then experience the joys of the British school system as teenagers, they had meltdowns about their peers using sophisticated vocabulary and with science not being a major subject in Austria, just a “Nebenfach” (side subject), their brains were reeling trying to get to grips not just with Physics but the language of Physics. And once again, the British education system (like most school systems) is based on a system introduced by the Victorians and let’s face it, what did the Victorians know about bilingualism?

However, in the UK they were able to do their German exams (GCSEs and A-Levels in German) early and this was great. In fact all kids with second languages are entitled do this – at the same time there were kids gaining recognised qualifications in Polish, Russian, Japanese and Spanish.

Language as an asset

If you look at bilingualism in terms of traversing education systems or using predictive text on your phone, it isn’t straightforward. If you look at life as a whole being bilingual or trilingual is a true gift.

Here is some advice on what you can do to raise your children bilingually:

-

Be consistent. If you are the parent responsible for a particular language, stick to your mother tongue. Even if your child answers you back in the local language and you speak that language fluently or with your partner. Just don’t budge!

-

Correct your child in a genteel fashion – the best way to do this is to repeat the incorrect sentence correctly, without pointing it out to the child. This is a bit tedious at the beginning as you may feel that every short exchange turns into a mammoth dialogue, but it really helps.

-

Expose your child to as much of the less present language as possible, this may be in terms of TV, films and books from the lesser predominant culture. Find ways of making the language attractive – watching films together, cooking, inviting friends over and speaking the language. Their friends will often find having a bilingual friend rather exciting. Talking to them is really important.

-

Keep family ties going with trips to their “other” culture(s) in the holidays (COVID has made this difficult) and with Facetime & co, it’s easy to stay in contact with grandma and grandad or other relatives across the seas. Try and get a relative to read a bedtime story via Zoom.

-

Maybe your child can gain recognised qualifications in a language in the country you are residing in. In the UK it is possible to do a GCSE in most languages and although the school can’t provide all the teaching, they are usually more than happy for pupils to gain qualifications in their mother tongue.

-

Seek advice and support if you are finding it difficult. There are plenty of books, blogs, TED talks on the subject. And if you have a child with learning difficulties, I would definitely talk to a specialist. Sometimes three languages, for example, can be too much to cope with.

Global Mindset and Brain Plasticity

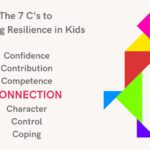

Being multilingual is a great skill for future employers and companies love them! The neuroplasticity of bilingual brains is extensive. They are flexible, open-minded, empathetic, inclusive and very useful team members as they see value in and create synergy from different ideas and approaches.

Gone are the days when bilingualism was frowned upon – the tut-tutting of immigrants using their language on public transport or when parents of bilingual children were told by kindergartens and schools to speak the local language at home. This was based on pre-1960s flawed studies which implied that bilinguals had a lower IQ than monolinguals, implying that their development was slowed down as a result of constantly having to distinguish between the two languages.

These days being ahead globally means having both knowledge of foreign markets and speaking foreign languages.

So being bilingual gives you a step ahead – and it’s okay if your kids are not perfectly balanced bilinguals. They are often the best international communicators as they know how to adjust their language depending on who they are speaking to, being inclusive. The effort and hard work you as a parent put in in their younger years is definitely worth it in the long run. And one day, they’ll thank you for it.

Victoria Sponge Cake

Vanessa shares a recipe for a quintessential British cake with us. A Victoria Sponge is light and easy to make (but beware! it’s messy to eat).

The funny thing is that this expert expat couldn’t decide if she wanted to share a recipe for Austrian Linzertorte or British Victoria Sponge. Each cake representative of a language and culture within her.

I am thrilled to host fellow global mobility professionals as guest bloggers. Today’s contributor is Vanessa from PAISLEY COMMUNICATION. Currently living in the UK but with 20 years lived experience in Austria she shares her research and personal experience raising bilingual children.

About the Author

-

How to move abroad with childrenJune 15, 2022/0 Comments

How to move abroad with childrenJune 15, 2022/0 Comments -

-

May on the Move 2022 – Sharing Experience of Global LifeApril 30, 2023/

May on the Move 2022 – Sharing Experience of Global LifeApril 30, 2023/ -

Life and Happiness Advice to my Younger Expat Partner SelfFebruary 10, 2023/

Life and Happiness Advice to my Younger Expat Partner SelfFebruary 10, 2023/

Tags

Newsletter Sign Up

Sign up below for monthly newsletter and download: helpful list of meal ideas for stressful times and recipes for delicious dips you can whip up for your next housewarming or farewell party.

Because sometimes, we need things to be a little easier.

WordPress – Global Mobility Trainer